[The following text includes fragments from conversations, emails, letters, postcards, and phone messages with Kathy Acker. There are also passages from her published work and from mine.]

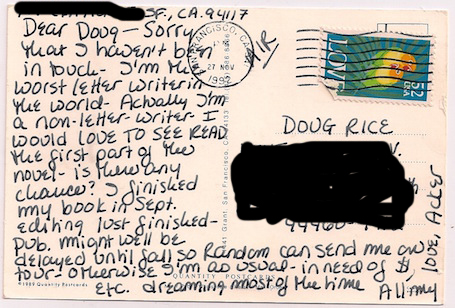

My friendship with Kathy Acker was most often little more than a string of long nights on the telephone. Miles and miles of roads and wires. Writing each other in and out of our bodies. Desperate longing. Locked inside being so far away from each other, Kathy and I became lost to space and time. “Come to San Francisco, Doug.” Her voice trails off. “Teach at the Art Institute with me. Here you can be free. Escape Ohio. Turn away from that fascist dean. Here, you can begin to think again.”

Late in her life, Kathy wanted nothing more than to cut her body into pieces. Small pieces that would stop the dying, the dying that ravished her body. An ancient, festering wound of incompleteness that threatened to replace the violence of sacrifice in her body with the ritual of purification. To seek. To lose. “If I remove my breast, this pain will go away. This coming death will flee.” But in Tijuana death is more resilient. It lingers all through her body. All through her life, Kathy had written endlessly about dying but did not die. Now on the inside of dying, Orpheus descends. The herbs fail.

We had lived each day in the kind of oblivion that can only create identity, that can only break and turn into a song. A tiny song that moves in the breeze, that cuts through berry patches. Blue stains on our shirts that want to cry but can find no tears. Just a tearing into a silent body. Write from the inside out. Do not hesitate until the flower bleeds. The anxiety of the Orchard. The scent of eucalyptus near her thigh. Jasmine behind her ear. For her breath that haunts my skin. I open my voice. Loose and abandoned words that want to be somewhere.

“I would like to write you so simply, so simply, so simply. Without having anything ever catch the eye, excepting yours alone, ... so that above all the language remains self-evidently secret, as if it were being invented at every step, and as if it were burning immediately."--Jacques Derrida

They will make you impure. Our personal histories written on filthy rags that are barely legible and that exist without language. Keep your wounds alive to the ghost of my innocence. To come to your touch in the night without words.

Near midnight Kathy and I walk into the city. We pick up what others have thrown away. We fill our pockets with discarded moments from the lives of thoughtless people who drop their memories on concrete. Paperclips, rubber bands, soiled paper. Dusty locks of hair. A perfect tomato. We think of knocking on doors to find the owner of the perfect tomato. But then Kathy bites into it. Her gold tooth in red. In our dreams we somehow get away. Without knowing. We stand outside Barneys looking in the display window like children with all their wanting and their laughter. Her leather coat like some other skin that covers her, that warms her, that saves her. She tugs at my sleeve. “Look at the green of that blouse, Doug.”

There’s a lot that we do not see.

“I will tell you what I will do and what I will not do. I will not serve that in which I no longer believe, whether it calls itself my home, my fatherland, or my church: and I will try to express myself in some mode of life or art as freely as I can and as wholly as I can, using for my defense the only arms I allow myself to use -- silence, exile, and cunning.” --James Joyce

Kathy taught me to dream. The map of dreaming. To enter, Kathy says, the water world of dreaming. Lost children inventing pain. Kathy’s red book. The triangle patch of dark grass. Wanting for love. My heart betrayed. This wanting that came down to the place of words. For her to seize my bones. My need for disease like a prayer to make my body into a foreigner. This return to the damp concrete of unforgiving basements. My own walking through streets in Sacramento now makes me become a prey to this fever of memories. Come home, little girl. To my hands. His smile. I am not afraid of my mother, father. Kathy writes. But she cannot stop. Her cheeks burn. He led her down this road. Her heart a traitor. But this longing that carries our bodies into the river.

“I will forever be writing my thoughts without order,” Kathy tells me, “without respect for your need.” She feared she would fall. She feared she would open her eyes and see her father one more time. Her mother pushing her away into another dark room. Locking her in dormitories for disobedient girls learning to be quiet. Boarding schools that discipline the beauty of soft skin into broken memory. I want my father to know my father. (Kathy resisted grammar and did not know what she meant.) Her mother forgetting and forgetting until the act of forgetting became her only memory. On many occasions she had forgotten Kathy’s name. Her mother with her knives and her pills. “Please take the pill that makes you funny, mother. The one that lets you kiss me goodnight.” Curled up tight. Not knowing how her mother’s fits of rage, fits of humor would write themselves onto her skin. To make them into sins of her past. Aimless threats. “I dream myself inside sex shows. There I am alone. Always telling myself who I am.” Fathers stare at my body. Reach toward my naked skin. It’s like traveling. Between.

In this world without end. I thought Kathy would live. From this day forth. Kathy will live forever. No beginnings. Only a world with Kathy. So I never thought to take a photograph of me with her. I did not want her presence. Those slight marks on some frail paper. She would be here. Present. Years later, Matias tells me that he, too, has no photos of Kathy. Just these marks.

“When the starry sky, a vista of open seas, or a stained-glass window shedding purple beams fascinate me, there is a cluster of meaning, of colors, of words, of caresses, there are light touches, scents, sighs, cadences that arise, shroud me, carry me away, and sweep me beyond the things I see, hear, or think, The "sublime" object dissolves in the raptures of a bottomless memory. It is such a memory, which, from stopping point to stopping point, remembrance to remembrance, love to love, transfers that object to the refulgent point of the dazzlement in which I stray in order to be.” --Julia Kristeva

From the first moments of our friendship, we spoke in tongues contaminated by years of reading and longing. “I want to find a way in. I want to understand the brutality of being in love with some man that I have met in an orchard and whom I can only understand as a vague abstract body in that state of being where only sex matters.” In Germany, Kathy drives her motorcycle into the trees. Fallen apples. She nearly slides off the road into the deep snow. Finds him standing there. A dark forest. Still. The smell of a river. I am sorry this is not you, Doug. To live without meaning. Beyond the comfort of words. Following into this desire. Bone. An uneasy song becoming noise.

Beneath the needle, inside the pain of cancer, Kathy invented someone to help her make her body.

I forced myself to do what I wanted to do.

“When Kafka allows a friend to understand that he writes because otherwise he would go mad, he knows that writing is madness already, his madness, a kind of vigilence, unrelated to any wakefulness save sleep's: insomnia. Madness against madness, then. But he believes that he masters the one by abandoning himself to it; the other frightens him, and is his fear; it tears through him, wounds and exalts him. It is as if he had to undergo all the force of an uninterruptable continuity, a tension at the edge of the insupportable which he speaks of with fear and not without a feeling of glory. For glory is the disaster.” --Maurice Blanchot

“I am in my body now,” she said. A recording, the echo of her voice, left on my answering machine. Oct. 2nd, 1997. Last words. Lost words.

I don’t want to be this monster any longer. To be a loner on the rim. To live in parking garages. I want to be able to live without swallowing one more thing. Her mouth wanted to become disobedient.

It took Kathy forever to hang up the phone. Don’t leave me like this. Now without her voice here I wonder if she has escaped. She said she could see doors. All along Revolution Boulevard we stumbled in and out of consciousness.

In death, orgasms change.

(To be continued in another blog.)

“By believing passionately in something that still does not exist, we create it. The nonexistent is whatever we have not sufficiently desired.”--Franz Kafka

_______________________________________________________________________________

To stay up to date with news about forthcoming publications, readings, gallery shows, and special offers, subscribe to the Doug Rice Newsletter.